"Report relayed from CS Altamonte in Terra Quadrant,” said Comm Officer Wilks, his boyish face lighting up the map room’s comm terminal. “Message from Captain Winnagard, recorded on one-three-nine.”

Bellegarde nodded. “Very good, Mr. Wilks. Transfer it here.”

“Aye, sir. Transferring.”

Bellegarde and Tolwyn had been sitting in the map room all morning and had already poured over holographs of Vega Sector and had sorted through reports from the ships positioned along the Kilrathi border and those searching for the Olympus. Now with a terse voice command, Bellegarde brought up a holographic map of Terra Quadrant. Sixteen star systems glimmered overhead, varicolored spheres with tiny, mottled planets rotating on their axes and orbiting their stars in real time. Yellow lines spanned the distances between stars and intersected flashing blue jump points. Bellegarde counted four clusters of green dots in the quadrant, each cluster identifying a Confed battle group. He ordered the computer to zoom in on a cluster between Murphy and Sirius systems: the CS Altamonte battle group.

Tolwyn blinked hard to clear his eyes, then glanced up at the display. “What do you think, Richard?”

“Winnagard’s gone out of her way to contact us. She’d turn in her own father for breaking regs, and she wouldn’t report out of sector unless--”

“She has bad news,” Tolwyn finished.

Bellegarde nodded, then turned to the comm terminal, where a data bar told him the transfer had completed. He tapped a key, and the message began.

Captain Heidi Winnagard’s grave look added nearly a decade to her forty-five years, and her bloodshot eyes contributed a year or two. She smoothed back a few stray locks of her generally disheveled hair, then sighed and said, “Admiral, we’ve lost contact with the destroyer Horatio Marx. I sent her out on patrol after we jumped into Sirius on one-three-three. Ten hours later, I dispatched a fighter patrol for SAR. We’ve lost contact with them as well. I’ve pulled my battle group clear, notified Admiral Chigaha, and have initiated long range scans. We don’t pick up anything, not even residuum from the destroyer and fighters. I don’t know what’s going on, but maybe the Horatio Marx stumbled into your renegade ship, the cats, or something else, which is why I’m reporting out of sector. I’ll continue my patrol here until I hear from you. Winnagard out.”

“What would Aristee be doing near Sirius?” Bellegarde asked. “Were I her, I’d jump out as far away as I could to buy time for repairs. I might even head to a Border World. Or maybe that missing Kilrathi supercruiser is responsible, though Intell informs us that she’s operated by the Caxki clan, which recently seceded from the emperor’s new alliance. I doubt that ship is at the emperor’s beck and call.”

“What disturbs me more is the lack of evidence.” Tolwyn brought his coffee mug to his lips, eyed the dregs, then thought better of finishing. “If Aristee took out the Horatio Marx with her hopper drive, there would still be gravitic residuum and traces of debris. And if the cats were responsible, we’d find a lot more.”

“Something’s interfering with Winnagard’s scans.”

“Maybe.” Tolwyn set down his mug on the console and slid his chair a meter left to the comm monitor. “Space Marshal Gregarov’s field office,” he told the computer.

“Connecting.”

“Yes, Admiral,” the space marshal said, seated at her desk before a semicircle of palm-sized data displays.

“Where are those two extrakinetic Pilgrims you conscripted? I read your special order, but they’re assignments hadn’t been posted at the time.”

“One is aboard the Bristol Mary in Roan Quadrant, the other is on the Zhou Chen in Petrov. Why do you ask?”

“Winnagard lost one of her destroyers near Sirius. Could be Aristee. I want to send a ship there with an extrakinetic Pilgrim on board.”

“It’ll take some time, but we can--”

“Those two Pilgrims are too far out. I think the Mitchell Hammock and Oregon can handle the situation at Triune for a while. Strike bases there have resumed full operations.”

“I know what you’re thinking, Geoff, but we agreed to hold Lieutenant Blair in reserve. His loyalty to Commodore Taggart makes him--”

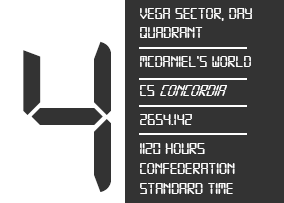

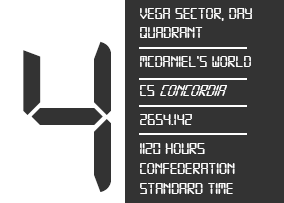

“What? A traitor? Even if Paladin has defected, I’m confident that Blair will act in our best interests.” Tolwyn looked askance at control panel. “Give me the map of Day Quadrant,” he ordered the computer. “Plot travel time from Hell’s Kitchen to Sirius.”

“Displaying map. Plotting coordinates.”

The representation of Terra dissolved into a string of jump lines between the aforementioned systems. Bellegarde skimmed the data bar below. “The Claw can be there in nineteen point three hours, Admiral.”

“Excellent.”

Gregarov shook her head emphatically. “Not Blair. Not when we have--”

“Two others who can be trusted more? They’re civilians, and you’re basing their loyalty on Alhoulouza scans.”

“And the jury’s still out on that technology,” she said through a wicked grin. “Which is why we’ve, well, I don’t want to get into the details. Suffice it to say that we’ve taken measures to assure that they cooperate.”

Bellegarde looked away in disgust, though he shouldn’t be amazed that the old lady would resort to coercion. She had probably “taken measures” over breakfast while reading casualty reports.

Tolwyn drew up his shoulders and hemmed. “Ma’am, despite your assurances, I recommend that we order the Tiger Claw to Sirius. Mr. Blair will confirm whether Aristee is or was there. Or we can send in the Altamonte and her battle group, though we might lose them as well.”

“Or you can wait, and we’ll send in the Bristol Mary or the Zhou Chen.”

“Either ship will take twice as long to get there,” Bellegarde interjected, reading his map.

“You said it yourself, ma’am. We need a swift and peaceful solution to this crisis.” Tolwyn dropped his voice to ominous depths. “Our resources are strained. We have to act now.”

“All right then. Send the Claw to Sirius,” she conceded with a snicker. “But I will log my reservations. And by the way, I presented my arguments to the senate regarding your order to destroy the systems and enclaves on one-five-eight. They agreed that maintaining the threat might bring about Aristee’s surrender. She’s got sixteen days. If she doesn’t stand down by then, you won’t be destroying anything. In fact, our no fly zones will come down, and we’ll begin aiding those people in any way we can. The order comes from President Vasura herself, and it’s already been endorsed by the senate.”

Tolwyn nodded microscopically, and his voice sounded just shy of a whisper. “So we’ll admit that threatening the Pilgrims was a grave error, issue an apology, give them aid, provide homes for refugees, and rebuild.” He suddenly chuckled, rose, then wandered away from the terminal. “I fail to see how that will get you your hopper drive and Aristee’s head on a spear. Our guard will be down. She’ll strike again. And this time, she might have the Kilrathi in tow.”

“Geoff, you and the Commodore have, with your no-fly zones and threats of Pilgrim genocide, created a public relations nightmare for the Navy. It will all come to an end on one-five-eight.”

Had Gregarov been in the room, Bellegarde may very have charged at her; instead, he opened his mouth--

But the admiral spoke faster. “Ma’am, we’ve done the best we could with the mess you handed us. The moment you learned that Aristee was planning on fitting her ship with a modified hopper drive, you should have moved in and arrested all concerned. You watched them build that drive. You gave her the means to kill six million people on Mylon Three, and thousands more have died since then. Don’t talk to me about a public relations nightmare. I’ve a mind to testify before the senate and present hard evidence of everything that’s transpired. I mean everything.”

“You’re free to jettison your career. But you won’t touch mine. You have no idea, Geoff. You really don’t.”

“Then enlighten me,” Tolwyn cried.

She averted her gaze to one of the monitors she had been reading. “Don’t you have orders to record and a communications drone to dispatch? I suggest you get to that. Gregarov out.”

“Goddamned bitch,” Bellegarde muttered.

Tolwyn gazed vacantly at the terminal, then suddenly jerked toward him. “Richard, you make that recording for the Tiger Claw.” He darted purposely for the hatch.

“Where are you going, sir?”

“To my quarters. I’ve got a hunch that won’t wait.”

“Sir, if I may ask--”

“You may not. But you’ll be the first I tell.”

The Synchronous Immersion Research Environment simulator (SIRE) represented a culmination of over six centuries of research and development and afforded Confederation fighter pilots with an experience that was, in every way, absolutely no different from actual combat. Though codes protected against it, any of the six SIRE units aboard the Tiger Claw could be programmed to actually hurt or even kill its pilot. And squadron commanders occasionally used that threat as a way to motivate lackadaisical rocket jocks.

The SIRE’s composite design, one of its true beauties, allowed it to mimic the cockpit of any starfighter in the Confed’s arsenal. And not only did the SIRE look and feel like the actual craft, but it also boasted the real-life Tempest targeting and navigational AI packages instead of replicas designed specifically for the simulator.

Christopher Blair, like any other pilot in the Confed Navy, knew that the key to a successful combat system is its ability to exchange information with its pilot and create a simbology between human and machine. The system must understand the pilot by monitoring physical and mental workloads. The system must adapt to the pilot’s condition and change the way it delivers and accepts information. Blair could throw a toggle, issue a voice command, or even think about what he wanted his Rapier to do, and the computer would initiate the command, though he hated the notion of having a combat computer worming through his thoughts and found the system too fast to allow for second-guessing, despite its ability to sort through and prioritize mental requests. Blair and many other pilots felt more comfortable taking the machine out of that loop. Jamming down a primary weapons trigger to cut loose a life-taking salvo provided the necessary and correct adrenaline rush that no cerebral interface could replace.

But during the Pilgrim war, space combat had barely yielded a raised pulse, let alone an adrenaline rush. High priority targets were usually attacked from great distances, and fighters rarely engaged each other in visual confrontations. It had all been done via reconnaissance and long-range ordnance. Wingmen would operate hundreds of kilometers apart from each other and trick attacking starfighters into believing that only a single target existed. Sure, Confed pilots sometimes went head-to-head with their Pilgrim adversaries, particularly during the battle for Peron, but more often that not, engagements had been highly impersonal. Then along came the Kilrathi, who took pride and honor in facing their combatants, and their instincts drove them in close to taunt their enemy and douse themselves in the light of their enemy’s destruction. Though most Confed pilots would never admit it, they secretly thanked the Kilrathi for returning their profession to its visceral roots.

Blair slid into the SIRE’s Rapier cockpit, still boiling over the fact that after training for six hours per day for four straight days, he had been instructed by Angel to endure a another six-hour marathon. She had told him he would train for “a few days” to test his reflexes--not a business week.

Thus far Blair had gone up against nearly every Kilrathi adversary the computer could muster. He took on Dralthi, Salthi, Krants, Grathas, and Jalthi. He flew with the other pilots in his squadron against Ralari-class destroyers and Fralthi-class cruisers. He swooped down and strafed Snakeir-class superdreadnoughts and even single-handedly took out a Kilrathi ConCom ship by tricking its captain into lowering shields. Everything about the simulations was as real to him as his own flesh and blood.

Which was why he now walked the fence between total exhaustion and collapse. Angel had been intentionally wearing him down. Why? He wasn’t sure. Maybe she didn’t want to show partiality to him since Captain Gerald and the rest of the squadron knew they were sleeping together. So she overcompensated by torturing him and had even refused to see him for the past four days. According Shotglass, the Claw’s resident bartender, she had rarely been seen outside of her quarters.

The cockpit suddenly glinted with an image of the flight deck. Rapiers and Broadswords lined both sides of the runway like a mechanical contingent welcoming a dignitary.

“Computer? Skip launch sequence. Mark for positive one minute into simulation.”

“Skipping launch sequence is not recommend because--”

“Initiate command.”

The view through the canopy immediately darkened into the star-specked void encompassing Netheranya. The fuel indicator bar glowed full overhead, and beside it, current speed stood at 178 KPS. Armor and shield indicators registered in the green, as did the neutron cannon and laser weapons systems. Missile systems read nominal. The words NO INTERNAL DAMAGE flashed in the left Visual Display Unit. Blair’s radar scope showed a dozen Rapiers at his six o’ clock, and IDs of each pilot scrolled up on his tactical display. He skimmed the roster to discover that Angel was not part of this exercise. Guess I’m wing commander again. Should I be excited?

Slumping a little and unable to suppress a loud yawn, he slid the Heads Up Display viewer over his right eye and waited for the computer to throw something at him. What would it be today? A squadron of Dralthi? A corvette?

“Receiving short-range communication from Tirida-class civilian transport vessel,” the computer said.

“Show me.”

“...and we don’t care what you do to us,” a young woman with a dirty face and stringy brown hair pleaded. “Just come for us. We surrender.” She sat at the transport’s helm and coughed as smoke from the shattered console beneath her wafted into her face.

I’ve seen this woman before, back on the Olympus. Damned computer pulled her out of my thoughts. I was wondering when they’d get around to testing me against Pilgrims. Do they really think this is an adequate test of my loyalty when I know this is a simulation?

The right VDU spilt to show Maniac’s masked face. “Got the skinny on our neighborhood fanatics. Stole that transport from a private pad on the west side of Triune. Looks like they took conventional fire on the way out. LSS is torn up pretty bad. They’re venting atmosphere. Can’t get a reading on their reactor, though. Shields up to full power in that quadrant.”

“Copy that,” Blair said, unable to lower his smile. The computer mimicked Maniac perfectly, peppering his voice with the exact amounts of conceit and sarcasm that reinforced his guard. Blair switched to the squadron’s general frequency. “Listen up. We got a stolen civilian transport in the AO, about twenty-thousands Ks out, bearing on your scopes. Maniac, Sinatra, and Cheddarboy? You’ll come with me for a look. The rest of you break to flanks and set up a defensive sphere, one klick maximum. Bug eyes for an ambush. Questions?”

“Just one, mate,” Captain Ian “Hunter” St. John said, his mask off, a cigar stub clenched in his teeth. “What’s the delay?”

Blair smiled. The computer had the big Australian pegged. “Break and advance.”

As he throttled up to 325 KPS, with Sinatra and Cheddarboy at his wings, the other fighters fanned out behind him. Blair switched to the transport’s frequency. “Attention. You are in violation of a Confederation no-fly zone. Surrender your vessel immediately.”

“What do you think we’re doing?” the woman cried. “If we don’t get some help in a couple of minutes, the children are going to die. We’ve only got three environment suits and about five minutes of air left. Of course we surrender. Help us!”

“Computer? Set nav point. ETA?”

“Twenty-one seconds.”

“Initiate thermal and electromagnetic scans of transport and long-range sweep for other vessels.”

“Initiating.”

“Passenger count?”

“Sixteen adults, eleven children.”

“Shit.”

“Why are you swearing, Christopher? It’s only a simulation.”

Blair smirked at Merlin, who now lay back on a futon of air just above the right VDU, hands clasped behind his head. “Don’t bother me now.”

“You’re going to fail this test, Christopher.”

“There’s a crack in your crystal ball. Now get out of here.”

The old man shook his head sadly, then rolled over to vanish.

“Tallyho,” Sinatra said in his usual monotone, a consequence of being demoted and reprimanded too many times to care anymore. Because he never held back a punch--even with superiors--he had taken more than his share of jabs, figuratively and literally. “Coming up on her now, Lieutenant.”

Rectangular, with a hammerhead bow, stubby forward wings and a quad-wing tail assembly, the transport limped slowly toward them at a pathetic 22 KPS. The dark, jagged stitching of conventional cannon fire traced from amidships back to her ion engines. Opaque gas spewed in tiny jets from more than a dozen breeches--way too many for Blair and company to affect an extravehicular repair in time.

“Uh, sir?” Cheddarboy began, gulping between words. “There’s uh, nothing we can do for them. By the time we tractor them back, all of them except the three in suits will be dead.”

“Shuddup, nugget,” Sinatra said evenly. “You got another year of this shit before you gain enough experience to have a decent and respected opinion.” Then he hailed Blair on the private frequency. “Lieutenant? The kid’s right. And there’s no way we can get a troopship out here in time.”

It took a moment for Blair’s thoughts to catch up with his pulse. Why would Angel do this? Why would she program a no-win situation? Or maybe she hadn’t.

Maybe the Pilgrims already knew they were dead.

Blair lunged for the comm control and punched up the general freak. “Everybody get the hell out of here! Light ‘em and go, go, go!”

“What’s happening, sir?” Cheddarboy asked.

“Just bug out!” Blair cried as he yanked his control yoke toward his chest, pulling in a high-G loop that rendered him inverted and in full retreat. He ignited his afterburners as--

“Aw, shit,” Maniac shouted. “Reactor overload. Shields dropping. Scanning interior. They’ve got class-nine planetary warhead in there. Trigger’s routed directly to the reactor. Ladies? Gentlemen? It’s been a pleasure.”

“Shuddup and move it! Move it!” Blair ordered. “C’mon. Throttles up. Bring ‘em to five hundred KPS. Push it. Push it!”

“Won’t matter,” Sinatra droned. “Shock wave will... here it comes.”

Blair glanced over his shoulder, into a silvery-white flash that pierced his eyes and suddenly darkened into a screen of blue. The flute player spoke to him in four-four time, in whole notes, in a tremolo that suddenly made him forget about the simulation.

Until someone’s hands unbuckled his harness, seized him by the collar, and wrenched him from the cockpit.

NEXT

|