“Torpedo room, conn,” Bellegarde snapped. “Status on planetary torpedoes one through thirty-six?”

“Conditions set for AXQ firing, sir,” answered Spaceman Second Class Oberson, a brown-haired boy of twenty with a glacier of a complexion and a voice like a squeaky wheel. “Torpedoes one through thirty-six loaded and spun up. Diagnostic almost complete. AXQ firing on your command. Zero hour in four minutes, twenty-two seconds. Mark.”

“Very well. Standby.” Bellegarde steeled himself as he eyed McDaniel’s World through the forward viewport. All of those blues and greens would soon turn to gray and black. “Mr. Wilks? Status on comm drones?”

“Data uploaded and sealed, sir. Fueling almost complete. Jump drive diagnostics found one anomaly. Drone replaced. Ready to launch in one minute, forty-five seconds. Mark.”

“Excellent. Recall our fighters from the Carraway. Standby to send message to Captains Boonesta and Lyndestal.” Bellegarde thumbed a switch on the ship-wide intercom. “Attention, this is Commodore Richard Bellegarde. By order of the Confederation Senate, Space Marshal Gregarov is hereby empowered to carry out a strategic planetary torpedo strike on planet ATZ seven-one-niner-three, AKA McDaniel’s World. At zero hour, comm drones will be dispatched to convey this order to our counterparts in the other systems and enclaves. This is a dark day for us all. Nevertheless, I expect every crew member to behave professionally. Your continued commitment will yield nothing short of victory. Bellegarde out.”

“Sir, comm transferred to ready room,” Wilks said.

“Very good,” Bellegarde replied, then slid out of his command chair. He crossed to the ready room, opened the hatch, and slipped furtively inside.

Gregarov sat cuffed to a chair at the comm monitor. Despite all she had been through, she carried herself with remarkable calm. Every hair remained in place, and her makeup appeared morning fresh. “I’m shocked and amazed, Richard. Not over how I’ve been treated but because you think I’ll help you.”

He fetched his sidearm from a shelf above the comm monitor, tugged it from the black leather holster, then focused the laser sight on her hip. “You’ll help.”

Though he had set the weapon for silent mode, it still issued a distinctive whir that made him flinch as much as she did. The round blasted through her leg, through the chair, then ricocheted off the deck and imbedded itself in the small oak conference table behind them.

“Shit,” she moaned, then tugged at her cuffs, wanting to nurse the bleeding wound.

Crossing behind her, Bellegarde pressed the pistol’s warm muzzle through her hair and onto the nape of her neck. She cried out as skin burned. “Order Lyndestal back to the Promise system, where he’ll begin bombing. Then you’ll tell Boonesta to resume her support position as we initiate our own strike. I know you’d like to curse me right now, tell me to go to hell or whatever other cliché you can muster. But let me save you some time and thought. I’ve already worked this out. I can blow your head off right now, wash my hands, have a cup of tea, bomb this planet, and go home--no questions asked. You’re fighting for your life right now, Sandra.” He removed the pistol and retreated to the hatch.

“Open channel to the Semoran,” she ordered the computer.

“Channel open.”

“This is Space Marshal Gregarov,” she told the Semoran’s comm officer, grimacing over the fire raging in her leg. “Get me Captain Lyndestal.”

As Bellegarde held his breath, Gregarov stiffened herself into composure and ordered Lyndestal back to Promise, then she contacted Boonesta and once more followed Bellegarde’s instructions to the letter. By the time she finished, a puddle of blood had spread beneath her chair. She ordered off the comm, then sneered at him. “Satisfied?”

Before he could answer, she began to convulse. After a few seconds of that, her eyes rolled back into her head, and she stopped moving.

Bellegarde cycled open the hatch and raised his chin to Comm Officer Wilks, on the opposite end of the bridge. “Mr. Wilks? Get me a med team in here ASAP.”

“Aye, sir.”

“The Semoran is pulling away,” Radar Officer Abrams reported. “Heading back for the jump point.”

“And the Carraway?” Bellegarde asked, aiming for the command chair.

“Shifting to starboard flank defense, sir.”

“Very well. Alert the battle group, Mr. Wilks. Standby.” He checked his watchphone. “Bombing will commence in T minus forty seconds.” He cocked his head toward the comm viewer. “Torpedo room, conn.”

“Conn, torpedo room. Oberson here, sir.”

“Are my birds ready to fly?”

Oberson read the status from one of his displays. “Conditions still set for AXQ firing, sir. All diagnostics run and complete. Targets designated and locked in. Torpedoes one through thirty-six ready to launch on your command. Warheads will be ready to arm at launch plus thirty. Arming codes ready to send.” The boy lifted a tentative thumbs up. “We’re good to go down here, sir.”

“Very well. Comm drones, Mr. Wilks?”

“Fueling complete. Navigation and jump drive systems programmed and locked. Just give the word, sir.”

“Anything on long-range comm sweeps?”

“Standard skipchatter, sir. We have not received contact from Amity Aristee or from anyone else aboard the CS Olympus. Lack of contact has been duly logged.”

Bellegarde nodded, then took in a long breath. He narrowed his gaze on McDaniel’s World and sat there, trembling for his bottle of Scotch.

“T minus three, two, one. Zero hour,” reported the XO from the port observation station. “Sir, it is now zero, zero, zero, zero on Confederation calendar date one-five-eight.”

“I concur, XO.” Bellegarde faced the viewer. “Conn, torpedo room. Launch first salvo. This is commodore.”

“Conn, torpedo room,” the XO repeated. “Launch first salvo. This is the XO.”

“Audio prints identified and matched. Authorization complete,” cried Oberson, his face washed in the green light of his monitors. “Launching first salvo.”

“Mr. Wilks? Launch comm drones.”

“Launch comm drones, aye-aye, sir.”

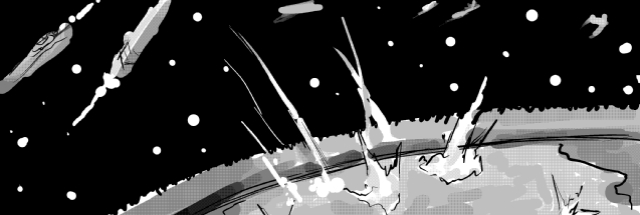

Though Bellegarde had never felt the preamble to a massive earthquake, the simultaneous launch of twelve planetary torpedoes and half as many comm drones came pretty damned close. The rumble woke in the lower decks, resounding slowly, then it matured into a powerful reverberation that slipped up the bulkheads and divided into a thousand tentacles of vibration.

“Torpedoes one through twelve away, sir,” shouted Abrams.

“Torpedo room, conn,” Bellegarde snapped. “Launch second salvo. This is the commodore.”

“Torpedo room, conn. Launch second salvo. This is the XO.”

“Launch second salvo, aye-aye,” hollered Oberson. “Firing!”

Abrams reported on the torpedoes’ progress, and Bellegarde went through the process a final time, silently asking for God’s forgiveness as the final tubes opened and torpedoes twenty-five through thirty-six blasted away, bearing Armageddon in their bowels.

“All torpedoes away,” Oberson announced. “Systems nominal. Guidance programs initiating target locks. Warheads arming in five, four, three, two, one.” He paused. “Warheads armed, sir. First detonation in approximately four minutes, thirty seconds. Mark.”

“Sir, several of the Pilgrim transports have begun firing on our escorts,” said Abrams, staring intently at one of his scopes. “It’s mostly low-level laser fire. No major threat to shields.”

“Mr. Wilks? Tell our skippers to hold their fire unless the threat becomes more significant. Even so, they’re to return only low-level fire.”

“Aye, sir.”

Bellegarde left his chair, staggered to the viewport, and gasped.

Thirty-six gray exhaust trails unfurled beneath the supercrusier and wandered out toward the planet, some veering to port or to starboard, some shooting up toward the north pole or diving toward the south, all preparing to tie the innocent-looking orb in a knot of devastation. You could talk about launching a planetary torpedo strike as much as you liked, but until you actually saw the raw power you had released, you would never fully understand. Commodore Richard Bellegarde understood very well now as he covered his mouth with a hand and waited for the first explosion.

Blair and Obutu watched from the Concordia’s aft observation bubble as the tawny glow of torpedo engines grew dimmer.

“Son of a bitch. He did it. He really did it,” Blair said.

“You thought he’d change his mind?” Obutu asked.

“I don’t know. Maybe I thought he wouldn’t have the guts to go through with it. He had four hours to think it over. I figured the guilt would set in.”

“Four hours, four millennia. No difference. He had his orders.”

“How many people you think are down there?”

“I don’t know. I really don’t.”

An icy sensation of awareness passed through Blair’s spine, a sensation so strong that it made him clutch the arms of his powerchair.

“Do you hear that?” Obutu asked.

Born from the hum of the Concordia’s ion engines and carried inexplicably through the vacuum of space, the notes of that familiar yet strange flute player echoed loudly through the bubble as a veil of blue haze descended upon the supercruiser.

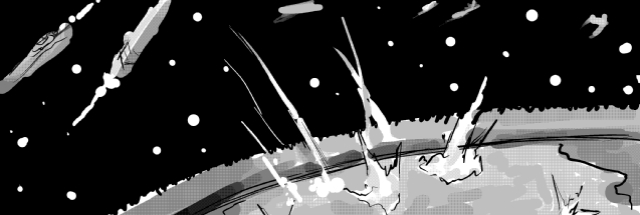

“Look at that,” Obutu hollered, pointing at globes of dark blue light that fell like meteors toward the planet.

One by one, the torpedoes chewing their way toward McDaniel’s atmosphere were struck by the Pilgrim globes. Multi-hued explosions blossomed in a perfectly timed and overwhelming display of power so unfamiliar and deadly that it left them rapt. As the last of the explosions faded, a series of secondary flashes drove their gazes skyward.

Hundreds of dark, undulating circles momentarily blotted out the stars until Pilgrim warships coruscated through them and sealed off the gravity wells in their wakes. The flashes worked their way down the sides of the night sky, then connected far below them like two swarms of fireflies clashing in battle.

In another blink, thousands of ships glided through the Sphere of Operations, some spreading out toward strategic positions to defend the planet, others darting in toward the battle group.

Obutu forced himself out of his chair, went to the thick Plexi, and raised his palms. “We’re sorry,” he said. “My god, we’re sorry.”

Grimacing, Blair wrestled himself out of his own chair to stand beside the XO. “They don’t hear you. But they have to.”

“Look down there,” Obutu said, pointing. “Bellegarde’s already launching fighters. Everything we got is pouring into the vac. He’s bringing the antimatter guns on line. You hear them?”

Blair nodded, then turned back for his chair. “Come on.”

“Where are we going?”

“If anyone can get through to them, it’s us. I mean, they are us. I say we go out there and give it a shot. We die, we die. But at least we go out in our fighters.”

Obutu cocked a brow. “We’ll never get on the roster. Not in our condition.”

“Like we need approval?”

Over two hundred Pilgrim warships now orbited Kilrah and exchanged torrents of fire with battle groups from each of the noble clans. A seemingly endless stream of combat reports flooded into the emperor’s meditation chamber at the apex of the imperial palace’s highest tower. The emperor had cloistered himself in the meditation chamber since the attack had begun, and clan elders demanded to speak with him because he had mobilized their forces before the Pilgrim attack--as though he had known it was coming.

Indeed, he had known. The Pilgrim protur Carver Tsu the Third had shown him the leaf, the fleet, all of it. The emperor had initially dismissed the evidence. But during Carver Tsu’s interrogation, he had learned that the protur whole-heatedly believed in the fleet and that he had no intentions of deceiving the Kilrathi; rather, he wanted to warn them that the Pilgrims were returning to collect their people within both Confederation and Kilrathi territory. Though the Kilrathi held only a few thousand Pilgrims as slaves and test subjects, the Pilgrims wanted to make sure that those people had the option to leave and that the Kilrathi would not interfere. The protur had said that these Pilgrims would, if provoked, neutralize the entire Kilrathi empire in one fell swoop.

But even the protur’s convictions had not fully convinced the emperor. It was not until an ancient Kilrathi ship had arrived on Kilrah, a ship that forced the emperor to consult the ancient journals of Sivar, that he finally understood. About three hundred years prior, a long-range Kilrathi scouting vessel had vanished in the Sirius system. That vessel now sat in emperor’s hangar, looking as new as the day it had been manufactured. The original crew of that ship had joined the emperor and Carver Tsu for a remarkable and unsettling meeting that had ended with the emperor’s decision to release the protur, James Taggart, and Amity Aristee. The emperor had done this as a sign of good faith, promising that his people would not resist the Pilgrim presence and that all salves and test subjects would have the choice to leave.

However, when it came to making promises that involved the clan elders, the emperor knew that those clans who had not joined his new alliance or had broken away from it would view the Pilgrims as invaders and launch unauthorized attacks. Those attacks would rally the others, and soon every clan would be involved. He had tried in vain prevent that from happening.

Another report came in, and the warrior who delivered it could barely get the words out of his mouth. Pilgrim troopships with hulls that resembled blue liquid were landing on the savanna and dispatching thousands of troops wearing translucent environment suits and firing weapons that immobilized Kilrathi warriors where they stood. Outer defenses had already fallen. Imperial guards could not hold out for much longer. The emperor’s own retinue, along with his personal guards, had reluctantly abandoned the palace without him because, as he had argued, a feeling rooted him to the place, a feeling he could not ignore. Now he leaned back on his hand-carved cathedra near the window, steepled his long fingers, and waited.

Footsteps echoed. Dor-chak rifles buzzed and faded. The sound of raindrops striking the stone floor drew closer, and music, human music, rose from the hall outside. He looked to the plastisteel door as azure light sliced through the cracks, outlining the barrier in a stunning glow. Then, with an inexplicable rush of steam, the door blew inward.

Five Pilgrim soldiers darted into the room. They carried semitransparent rifles with muzzles that yawned open as they were pointed at him.

I could have escaped, he thought. Why did I obey this feeling? Tell me, Sivar, have I shamed my people?

A woman with broad shoulders and straight, white hair rounded the corner and entered the chamber. “Stand down,” she ordered in perfect Kilrathi.

The soldiers brought their weapons to their chests and retreated two steps, creating a path for her. She came toward the emperor, her expression strangely soft. Her practiced Kilrathi bow startled him, and she even kept her head lowered until he released her.

“Who are you?”

She looked up, eyes widening. “I’m Sostur Hella Ti. We’ve come for you, Emperor.”

“Come to kill me? Then do it now. I’d prefer to die on my own world.”

“You tried to keep your promise. This isn’t your fault.”

“Who are you? You can’t be Pilgrims”--he pointed at one of the rifles--“not with this kind of technology.”

“You met with some of your people who’ve been with us. They didn’t lie. We are Pilgrims. And we’ve returned for our own.”

“Then take your people and go.”

“Were it only that easy.” She glanced to the ceiling. “Your kalralahrs have put our people in the middle of the firing zone.”

“I had no control over that.”

“Let us return control to you.”

He issued a long growl of contemplation. “You have my world. And from what I’ve seen, you’ll soon conquer the rest of our holdings. You suggest that I rule an occupied empire?”

“No.” She raised her brows. “Simply help us to help our people. Now, if you’ll come, there’s someone who wants to meet you.”

The emperor nodded, slid forward on his cathedra, then groaned as he straightened his old warrior’s frame. It took but the slightest effort to withdraw his zu’kara knife from its waist sheath. The old and sacred blade felt warm and smooth in his shaking paw.

No, I will no longer yield to this feeling. You say you will give me control, but you--and only you--have the power to give. I have nothing. And I will no longer shame myself, my people, or Sivar.

Knowing that further thought would undo his courage, the emperor jerked the blade toward his throat.

In the name of the noblest hari, the Kiranka, I give my life to you...

As the sharp plastisteel brushed the pale folds of his neck, a flash accompanied by an odd plop stole the weapon from his grip.

“I’m sorry, Emperor, but you still don’t understand,” said the woman, now holding his blade. “Come with us.”

“I won’t.”

“We offer you a chance to save your people, to prevent anymore bloodshed--including your own.”

She extended her index finger and flicked it at each corner of the room. Magnificently detailed holographs ignited and slowly rotated to show different battles within Kilrathi territory:

Kalralahrs fired upon each other as they argued over how they should handle the Pilgrim threat.

Missiles slashed across the sheet of space.

Warriors choked on their own blood seconds before their fighters vaporized.

The sheer numbers of dying Kilrathi left the emperor feeling angered, manipulated. Were it not for the Pilgrim invasion, his warriors might still be alive. He whirled to the window, slapped a thumb on the control panel, and the hemisphere of protective energy winked out. A gale blew in, backed by the deafening roar of troopship thrusters.

Squinting against the force, the emperor stepped onto his cathedra and launched himself out of the tower, praying that he would meet Sivar on the merciless pavement below.

A flash. A plop. And he found himself standing upright in the courtyard. It took a moment to orient himself, then he gazed out past the low palace wall to the hundreds of ships that had landed on the savanna. His eyes began to burn, and a deep, full-throated chuckle rose from his gut.

The Pilgrims had stripped him of everything, including the power to take his own life. Was this a lesson in what they called humility? Had they forgotten that he was anything but human?

As he backhanded the tears from his eyes, he heard the clatter of approaching soldiers. He spotted them, then looked up to the tower window, where Sostur Hella Ti leaned over and shook her head at him.

He answered her with a roar that echoed up to the war-streaked heavens.

“Grandfrotur!”

Joa Autumnsoul opened one eye as Ravi bounded into the den, the back porch door slamming behind him.

“Grandfrotur,” the boy panted again. “Come outside. You have to.”

The recliner felt especially comfortable this evening, and Joa’s old bones presented a convincing argument that he should remain exactly where he was. He had fallen asleep while watching the news, and he tried to remember why turning on the program had seemed so important. Suddenly, it came to him. He sat up, focused on the boy, and braced himself. “What do you see?”

“I don’t know. Come on.” Ravi grabbed his wrists and yanked him from the chair.

Wincing, Joa tugged one arm free as the boy led him out into the frigid night air.

“There,” Ravi said, pointing at a dense band of quavering blue dots that arced across the sky. “What are they?”

Joa opened his mouth, about to express his ignorance, but the longer he stared at the sky, the more familiar those radiant specks became. He heard the sad, lonely notes of a flutist, then gasped and fell to his knees.

“Grandfrotur, what’s wrong?”

“It’s some day,” Joa muttered. “It’s some day.”

“What?”

Joa lifted his hands and spread his fingers. “Those, Ravi, are Pilgrims.”

“The ones you told me about?”

He nodded.

“How do you know?”

He seized the boy and hugged him tightly. “Close your eyes... and listen.”

NEXT

|