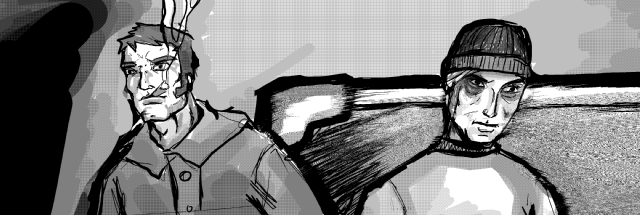

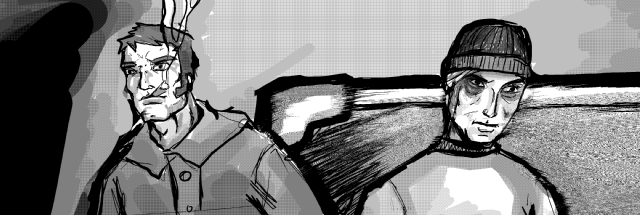

Hunter led Blair to the lower aft decks, to a storage room behind the repair bay. The techs working on the deck nodded to Hunter as though he regularly visited these parts. Blair glanced curiously at a few of the specialists, who quickly turned their attention elsewhere.

After keying in the hatch’s access code, Hunter gazed askance at Blair and said, “I just want you to know that it wasn’t our fault.”

The hatch opened, and a shaft of light sliced into the otherwise dark room. Walls of storage compartments standing just taller than Blair arrowed off for about ten meters, and to the right sat an open area to park the four-wheeled deckscrubbers and decksealers that now hummed along throughout the Claw’s lower decks.

Hunter advanced into the shadows.

As Blair watched him go, gooseflesh fanned across his shoulders. “Captain?”

“What are you standing there for, mate? C’mon.” After a few seconds of looking puzzled, Hunter smiled, and the sun finally rose in his gaze. “Ah, you think I’m luring you into this out of the way place so I can kick your ass. Don’t worry about me, Lieutenant. I still owe you for dragging me out of that gravity well. I’m not fond of Pilgrims, but anyone who puts down a Kilrathi invasion and saves my sorry ass is all right with me. Coming?”

Blair gritted his teeth over the decision, sighed, and moved on.

They traveled to the back of the storage room, turned left down a corridor running perpendicular to the walls of compartments, then took a right into a storage room nearly identical to the first.

The lights came on.

Maniac rounded a corner. “Hey, Blair,” he said solemnly, scratching the crown of his blond crewcut. “Before you see ‘em, I just want to tell you that, well, I guess I’m sorry.”

Blair plowed past Maniac, his gaze sweeping the area. “See what? What are you talking about? And why the hell are you sorry?”

But before Maniac could answer, Blair spotted them sitting on the floor, arms bound behind their backs, legs shackled with durasteel binders, mouths tapped shut. He didn’t recognize the three men. The fact that their cheeks bore purple welts and their eyes had swollen shut probably had something to do with that.

“Just three class-two welders whose parents fought in the first Pilgrim War,” Hunter said. “Thought they’d make the crime so obvious that it would fall between our eyes. They had pretty good alibis, but Maniac kept on their sixes and learned the truth. We confronted them, and that individual threw the first punch.” Hunter pointed at the nearest tech.

Blair hunkered down in front of the welder, who could not be more than twenty. The guy tried to stare at his visitor, but the effort caused him to whimper and tug against his bonds. Blair tossed a glance to Maniac. “What did you hear them say?”

“Heard ‘em talking about how much they hate Pilgrims, how a couple of them lost their parents in the war, and how it was a goddamned shame that the Confederation had even allowed Pilgrims to enter the military.”

“That’s it? You’re kidding me.”

“They had the equipment and the motive. What more do you want?”

“You idiot. Someone could’ve set them up.”

“You’re reading way too much into this. No one would go to all that trouble just to kick your ass.” Maniac’s eyes bulged. “This is a hate crime, and these three are definitely operating in the intelligence-free zone.”

Blair returned a scowl, then yanked off the tape covering the first welder’s mouth.

“You jocks’ll go down for this, I swear it,” said the battered young man.

“You didn’t beat me, did you,” Blair said.

“That’s what I’ve been telling your friends.”

“But what about your friends,” Maniac interjected. “They confessed.”

“They’d say anything to make you stop,” Blair retorted, then looked to the welder. “How long have you been down here?”

“I dunno. A day, maybe. I’m thirsty and starving. They haven’t fed us.”

Blair stood. “Let ‘em go.”

“No way,” Maniac said, then charged up to Blair. “I’m not going to back to the brig.”

“Yeah, you are.”

Maniac poked Blair with an index finger. “I did this for you. These bastards had it coming with interest. And don’t believe anything they say. They did this. They did it.”

Blair eyed the three welders. “Nope.”

“How do you know?” Maniac challenged.

“You weren’t there.” He regarded Hunter. “Question. Do Obutu or Angel know about this?”

The captain shook his head. “Techs outside have kept it quiet for us. But that won’t last long.” He frowned at Maniac. “Guess we’ll be turning ourselves in, Lieutenant. Can’t keep these guys here forever.”

Maniac spun away and swore three times, lifting his voice from a whisper to a shout. He pointed at the welders. “They started it.”

“This is so juvenile that I can’t believe I’m standing here,” Blair said. “And thanks for showing me this. Thanks for making me an accomplice. You guys are unbelievable. And I’m sorry, but if you don’t turn yourselves in, then I will.”

“We’ll take care of that,” Hunter said.

Blair glared at them. “I’m going to get some sleep. Maybe I’ll catch an hour before this particular pile of shit hits the fan.” He hustled off, muttering, “What else can happen?”

Even as the hatch to his quarters shut behind Blair, Karista’s voice rose from the silence of his mind. Then she appeared to him, as she had before, though she looked more ragged, and something in her gaze set off alarms that he tried to dismiss so that the guilt wouldn’t get the better of him. “Christopher, I’ve so much to tell you.”

“Wish I were in the mood to listen.” He dropped onto his rack and began furiously untying his boots. “Got my own problems now.”

“I know, but to be honest, they’re not very important. You have to start thinking much bigger than yourself because Ivar Chu and the other Pilgrims who set out for Sirius so long ago are coming to save us.”

“That’s nice. Tell ‘em I said hey. And I don’t really need any saving unless one of them feels like investigating a hate crime.”

“I’m serious. It’s taken me a couple of days, but now I have proof that they’re coming. And I need to get it to that admiral who wants destroy our systems because if he goes ahead with his plans, the Confederation will be wiped out.”

He snickered. “Wow, sounds serious.”

“Christopher, you’ve been having the visions again. I know you have. Every morning when you wake up you see blue. You hear the music and sometimes even the voice that tells you to be patient and to help whenever you can.”

“So you’re reading my script. I’m underwhelmed. Maybe we’re all just delusional.” He toed off the boots, then rose and slid out of his flight suit. “I want to take a shower. You’re not really here, but you kind of are, so you mind?”

“The Concordia is in orbit of McDaniel. I need to get my evidence to that ship.”

“Here we go...”

“I don’t think I have it in me to steal another ride and get it through the Confed’s no-fly zone. I’ve grown so cold and tired. You know yourself what it’s like. I need you.”

“Can’t you just carry the evidence to them extrakinetically?”

“Maybe. But once they have it, there would no one there to explain what it is. And carrying something that far might incapacitate me for a week. I need you to get me to that ship. I’ve done everything I can on this end.”

Thoughts circled, charged, evaporated, and were born in the seconds that Blair stood there, considering what she was asking. Even if he agreed to help, how the hell would he get through the no-fly zone and get planetside? It wasn’t as if he could fly his Rapier in, land, and tell her to hop in the backseat. Rapiers were not atmospheric craft nor did they have backseats. Then, of course, remained the “little” problem of getting permission to leave.

“Christopher. Please.”

No, he couldn’t turn down that face, those eyes. I’m not supposed to be in love with you. Angel would remind me of that. “I’ll see what I can do.”

“Don’t waste time. According to the news here, if Aristee doesn’t stand down and return the Olympus by Confed day one-five-eight, the systems and enclaves will be destroyed. The order just came in for a massive evacuation. They want to ease their consciences by saving some of us before they destroy our land. They think they can do that with impunity, but they have no idea how powerful the Pilgrims are.”

“Wait a minute. They’re evacuating the populace? Can you get on one of those ships?”

Her expression brightened. “I think so.”

“We’ll have to time this just right. I’ll calculate the jumps to get me there, but you’ll need to stay in touch. Wait a minute. What am I doing? If I don’t get permission--”

“Were I you, I wouldn’t waste time asking.”

“I can’t go AWOL. I’ll have to go to Gerald.”

“Just get here. The admiral has to see what I have.”

“What do you have?”

“Remember that woman I told you I was going to see? Suffice it to say that the trip really paid off.”

“I’ll need more than that to convince my captain.”

“All right. Close your eyes. And I’ll show you.”

He held up a palm. “I’ll need evidence I can share with him, otherwise we’re back to just my word.”

She sighed in frustration. “I can’t give you more.”

“Can you put whatever you want to show me in his mind?”

“He’s not a Pilgrim.”

The realization came slowly and fused with a chill. “Gerald’s no Pilgrim. But I know someone else on board who is.”

The environment suits supplied by the Kilrathi were at least twenty years old, and Paladin feared that the life support batteries would not hold a charge for long. Since the two guards with them had not been wearing translators, Paladin had been forced to mime his request for newer suits. One of the cats had heaved an exaggerated snarl, then had thudded away.

Ten minutes had passed. No new suits.

Poised at an airlock that separated the cellblock from an octagonal corridor festooned by conduits and thick with pale green nutrient gas, Paladin checked his life support and comm units one last time, did likewise for Aristee and the protur, then waved to another guard standing inside the lock.

“He looks thrilled to let us go,” Aristee said as the door hissed open.

“The word humility doesn’t translate into their language,” commented the protur. “But I’ve taught them what it means.”

“Care to say how?” Paladin asked.

“Patience.”

Paladin’s expression soured. “I hear that word again, I’ll be--”

“Sick?” Aristee finished.

“No. I’ll be forced to cut off the protur’s lips so that he can’t pronounce it.”

“Oh, James,” the protur said. “If only you’d just listen. And be--”

Paladin raised an index finger and scowled.

“--patient.”

About to launch into a tirade that would criticize every aspect of the protur, right down the sandals he wore beneath the e-suit’s boots, Paladin took in a deep breath, then the guard distracted him with a shaking of his head and wagging of his chin in a comical attempt to urge them forward.

They slipped into the octagonal corridor, where two more guards met and led them toward the broad doors of an elevator. Once inside, the lift carried them swiftly up for twenty seconds. Aristee complained that her suit was getting hot, but Paladin’s check of climate controls showed systems nominal.

The lift doors finally opened to reveal a modest-sized hangar shaped like a triangle with the top sheared off. Several Imperial shuttles floated in zero-G moorings about twenty meters ahead, their bronze-colored bows narrowing into a quartet of sharp prongs that housed their navigation and sensor packages. Beside them sat an antique scouting vessel in remarkably good condition, considering that it had to be at least three centuries old. Fifty or so meters beyond it, a pair of hangar doors parted with a tremor that rose into Paladin’s gut. One of the guards raised a massive arm and flicked out a long nail to indicate which of the ships was theirs. Then both Kilrathi turned away and slunk back toward the lift.

Aristee and the protur started for the shuttle.

“I’m not getting on board,” Paladin said, standing behind them. “Not until you talk.”

“It makes no difference to me whether you go or stay,” answered the protur without turning back. “And I’d tell you if I could. But I can’t. And that’s that, isn’t it?”

“Why can’t you talk?”

“It’s neither my place nor desire. And to be honest, I get a certain thrill from seeing you squirm. You, standing on your mountain of Confederation dung, believe that what you’re doing is right. You and all the others. You’re so lost. You, like the Kilrathi, will... be.... humbled.”

“James, I, uh, I can’t--” Aristee collapsed at the foot of the shuttle’s loading ramp.

He bounded to her, rolled her onto her back, then popped open the life support control panel on her lift wrist. The data bar for climate control showed all systems nominal, but her suit’s temperature had suddenly risen twenty degrees and continued to climb. He switched control to manual and pressed a button to bring down the heat. Damned old suits. No response.

“What’s wrong?” cried the protur, hovering over them.

“Get out the way,” Paladin shouted, then dragged Aristee up the ramp and into the shuttle’s wide hold. He set her down, then practically dove for the hatch control even as the protur hustled inside. As the ramp lifted to seal into the hull, Paladin sprinted to the cockpit, where he found a Kilrathi pilot and navigator in the middle of a preflight check.

“Seal the cockpit. Switch to Earth normal atmosphere in the hold.”

“We don’t like to do that,” said the pilot through his translator. “Your air promotes the corrosion of our instruments.”

“You were ordered to get us safely out of here. And this is a shuttle equipped for prisoner transport. If you don’t do as I say, one of your passengers is going to die. You’ll fail your duty. Where’s the honor in that?”

The big cat exchanged an unreadable look with his navigator, then cocked his head back to Paladin. “Sealing cockpit. Hold to Earth normal, twenty degrees Celsius.”

Paladin scissored by the cockpit hatch as it began to close. He felt a powerful wind tug at his shoulders and checked his external sensor as the pilot vented the nutrient gas and flushed the hold with seventy-eight percent nitrogen, twenty-one percent oxygen, and trace elements of argon, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, neon, and helium. The moment external readings flashed in the green, he unclipped and screwed off Aristee’s helmet. Her head fell slack. Perspiration soaked her hair. As he fumbled to open the collar of her suit, her eyelids fluttered open, and a strange look washed over her face. “James,” she said. “I saw them. You won’t believe it, but I saw them.”

Fear surged into Commander Obutu’s expression as Karista’s likeness flickered before him and Blair. She stood in Obutu’s quarters and looked quite comfortable with her surroundings, despite the fact that her flesh lay light years away. “Are you ready?”

“My God, I’ve never seen anything like this,” Obutu rasped. “Is that what you call her script?”

“Yeah. And we look the same on her end. We could leave this place and go to what we call the quilt, though I’m not sure you could visit it. I think you have to be an extrakinetic to go there.”

Entirely rapt by Karista’s image, Obutu barely managed a nod. “I thought you were lying.”

“Karista? Show us what you have,” Blair said.

Without warning, her image peeled away into a field of stars that encompassed the entire room. Even Blair, someone who had experienced the continuum and the quilt firsthand, felt insignificant and utterly awed by the vastness of the image.

And from that sweeping tableau emerged a grand fleet of ships the stole Blair’s breath. The vessels glowed a pale white that darkened to azure around their edges, and their fluctuating hulls resembled banners, pennons, or sheets driven through the wind. Some equaled the Confederation’s largest supercruisers in breadth and width, while others appeared so huge that Blair had trouble comprehending their size. He found himself floating between the magnificent vessels and sensed that they numbered in the millions, for their formation stretched back as far as he could perceive.

“This is just one of many Pilgrim war fleets,” Karista said. “It’s headed from the Virgo Cluster toward Confederation space. It’ll jump through the Sirius system and be here within five days. At least one other fleet is headed toward Kilrah.”

“Where did you get this information?” Obutu asked.

“From a woman here on McDaniel. The data is stored in the cells of leaves from her veracia tree. There are other trees just like hers growing on Faith, Promise, and a few in the enclaves. These Pilgrims wanted to let their own know that they were coming. We had a leaf analyzed. The data is like a real time link to them. When it’s accessed, we can get this close to them but no closer. The admiral needs to see this before he gives the order to destroy our systems and enclaves. The only way I can show him this is to have a leaf analyzed on board the Concordia. I need Christopher’s help to get there.”

“We’ll send word to the Concordia immediately,” Obutu said. “We’ll tell them that we have evidence they must see before ordering an attack.”

“But sir, a comm drone would be too slow, and the admiral could choose to ignore it. We need to get Karista to the Concordia within five days,” Blair pointed out. “I’ve already calculated the jumps. I can get in there in about four days using a LARP variant Rapier, extra oh-two, and cells. Admiral Tolwyn needs to have a leaf in hand to believe any of this. I’ve helped him before. I think he’ll listen to me.”

“I see. And you want to go now?”

“Yes, sir.”

In a wash of motion that left Blair astounded, the star field collapsed into the form of Karista. She looked at them for a second, then lifted her chin, squinting at something unseen. “There’s... there’s someone else who’s seen this.”

“What do you mean?” Blair asked. “I assumed others would know--especially Pilgrims on McDaniel.”

“I mean someone on board the Tiger Claw. There’s another Pilgrim here who’s accessed this. And he must be an extrakinetic because he’s managed to hide from me. I couldn’t see his face. But I felt him.”

“Another Pilgrim?” Blair asked dubiously. “And an extrakinetic? What are you going to say next? That the admiral himself is really a Pilgrim?”

“I’m serious, Christopher. There’s another Pilgrim on board this ship. And like I said, he must be an extrakinetic and doesn’t want to be discovered. I think he sensed what I was showing and couldn’t resist a look for himself.”

Another Pilgrim. Maybe like Obutu this Pilgrim had refused to reveal his heritage, and the present Pilgrim crisis only reinforced his decision. But something else about this revelation gnawed at Blair. He couldn’t put his finger on it.

Until he replayed the attack.

Now he remembered thinking that one of his assailants had to be using a gravitic weapon akin to a Pilgrim’s extrakinetic strength. But he had assured himself that there were no other Pilgrims on board the Claw, and he had been unable to explain why they would attack one of their own.

“All right,” Blair said, maintaining his disinterest, “So there’s another Pilgrim. So what. Commander, do you think you could convince Gerald to let me go?”

The intercom beeped.

“Yes?” Obutu answered.

“XO, report to the wardroom,” Gerald ordered.

“Speak of the devil,” Obutu muttered. “Sir, I want Lieutenant Blair to accompany me. We have an important request.”

“Good, I want to see the lieutenant, anyway. And so does Lieutenant Commander Jhinda. Seems a couple jocks from First Squadron took the law into their own hands. And it seems that Mr. Blair’s an accessory after the fact.”

Obutu’s gaze reduced Blair to a quivering idiot. He looked away, swore, then glanced to Karista, who had dissolved into the half-light.

NEXT

|